A new study by researchers from MIT and Empirical Health used 3 million person-days of Apple Watch data to develop a foundation model that predicts medical conditions with impressive accuracy. Here are the details.

A bit of background

While Yann LeCun was still Meta’s Chief AI Scientist, he proposed the Joint-Embedding Predictive Architecture, or JEPA, which essentially teaches an AI to infer the meaning of missing data rather than the data itself.

In other words, when dealing with gaps in data, the model learns to predict what the missing parts represent, rather than trying to guess and reconstruct their precise values.

For an image, for instance, where some portions are masked and others are visible, JEPA would embed both the visible and masked regions into a shared space (hence, Joint-Embedding) and have the model infer the masked region’s representation from the visible context, rather than the exact contents that were hidden.

Here’s how Meta put it when the company released a model called I-JEPA in 2023:

Last year, Meta’s Chief AI Scientist Yann LeCun proposed a new architecture intended to overcome key limitations of even the most advanced AI systems today. His vision is to create machines that can learn internal models of how the world works so that they can learn much more quickly, plan how to accomplish complex tasks, and readily adapt to unfamiliar situations.

Since LeCun’s original JEPA study was published, this architecture has become the foundation for a field that has been exploring “world models,” which is a departure from the token-prediction focus of LLMs and GPT-based systems.

In fact, LeCun even left Meta recently to start a company focused entirely on world models, which he argues are the real path to AGI.

So, 3 million days of Apple Watch data?

Yes, back to the study at hand. Published a few months ago, the paper JETS: A Self-Supervised Joint Embedding Time Series Foundation Model for Behavioral Data in Healthcare was recently accepted to a workshop at NeurIPS.

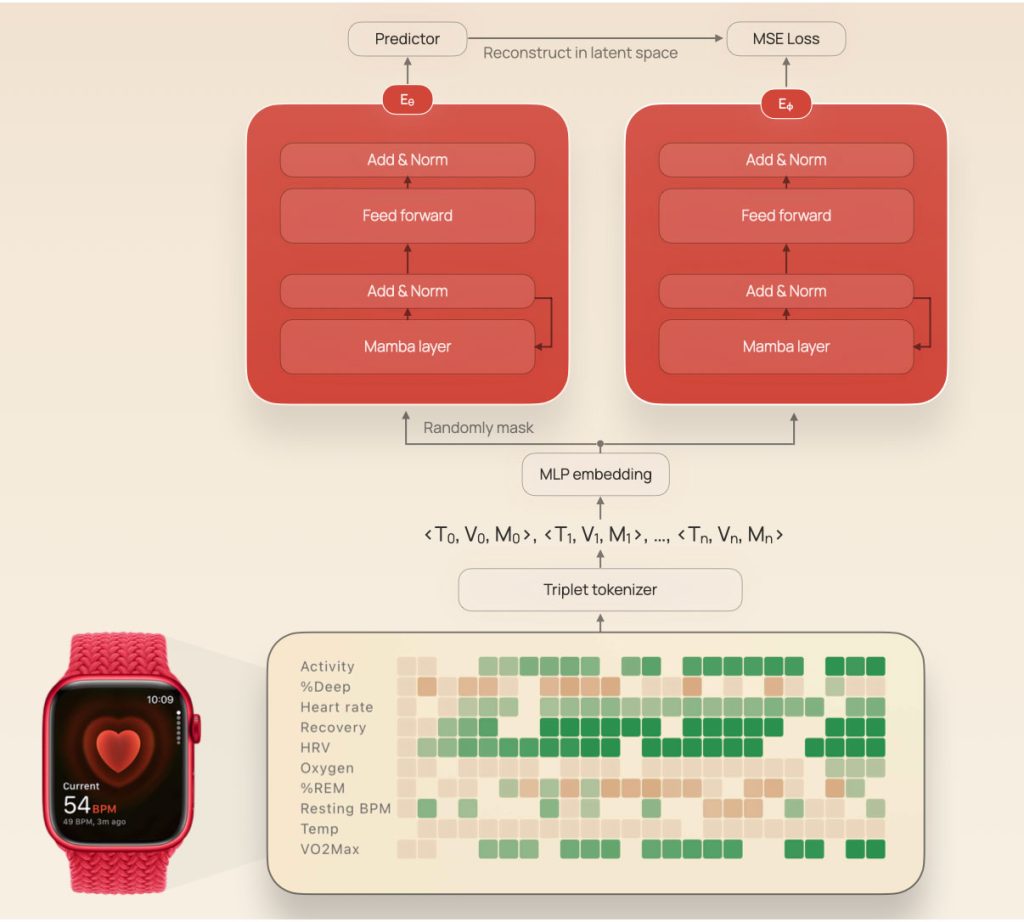

It adapts JEPA’s joint-embedding approach to irregular multivariate time-series, such as long-term wearable data where heart rate, sleep, activity, and other measurements appear inconsistently or with large gaps over time.

From the study:

The study utilizes a longitudinal dataset comprising wearable device data collected from a cohort of 16,522 individuals, with a total of ~3 million person-days. For each individual, 63 distinct time series metrics were recorded at a daily or lower resolution. These metrics are categorized into five physiological and behavioral domains: cardiovascular health, respiratory health, sleep, physical activity, and general statistics.

Interestingly, only 15% of participants had labeled medical histories for evaluation, which means that 85% of the data would have been unusable in traditional supervised learning approaches. Instead, JETS first learned from the complete dataset through self-supervised pre-training, and then fine-tuned on the labeled subset.

To make the whole thing work, they made triplets of data out of observations corresponding to day, value, and metric type.

This allowed them to convert each observation into a token, which in turn went through a masking process, was encoded, and then fed through a predictor (to predict the embedding of the missing patches).

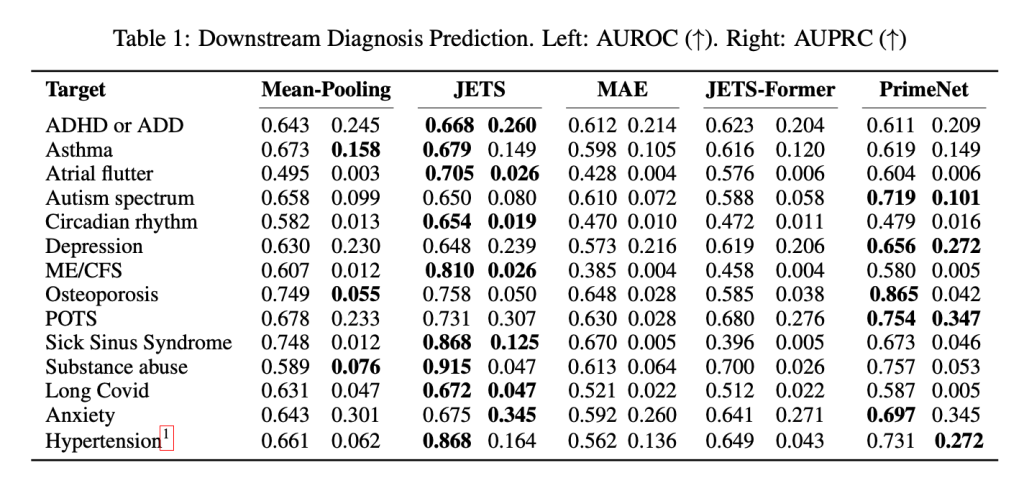

Once that was done, the researchers put JETS up against other baseline models (including a previous version of JETS, based on the Transformer architecture), and evaluated them using AUROC and AUPRC, two standard measures of how well an AI discriminates between positive and negative cases.

JETS achieved an AUROC of 86.8% for high blood pressure, 70.5% for atrial flutter, 81% for chronic fatigue syndrome, 86.8% for sick sinus syndrome, among others. Of course, it didn’t always win, but the advantages are pretty clear, as seen below:

It is worth stressing that AUROC and AUPRC aren’t strictly accuracy indexes. They’re metrics that show how well a model ranks or prioritizes likely cases, rather than how often it gets predictions right.

All in all, this study presents an interesting approach to maximizing the insight and life-saving potential of data that could be written off as incomplete or irregular. In some cases, health metrics were only recorded 0.4% of the time, while others appeared in 99% of daily readings.

The study also reinforces the notion that there is a lot of promise in novel models and training techniques to explore the data that is already being collected by regular wearables such as the Apple Watch, even when they’re not worn 100% of the time.

You can read the full study here.

Accessory deals on Amazon

- Wireless CarPlay adapter

- Logitech MX Master 4

- Apple AirTag 4 Pack

- AirPods Pro 3

- Beats USB-C to USB-C Woven Short Cable

FTC: We use income earning auto affiliate links. More.

Comments